- Home

- Blog

- Web Design Problems with Using Website Validation Services

Problems with Using Website Validation Services

-

13 min. read

13 min. read

-

William Craig

William Craig CEO & Co-Founder

CEO & Co-Founder

- President of WebFX. Bill has over 25 years of experience in the Internet marketing industry specializing in SEO, UX, information architecture, marketing automation and more. William’s background in scientific computing and education from Shippensburg and MIT provided the foundation for MarketingCloudFX and other key research and development projects at WebFX.

Amongst the basic skills that fledgling designers and developers should know is the art of website validation.

Website validation consists of using a series of tools such as W3C’s Markup Validation Service that can actively seek out and explain the problems and inconsistencies within our work.

While the use of such tools has benefits (in the sense of being an automated fresh pair of eyes), a worrying trend of either over or under-dependence keeps rearing its ugly head.

This article aims to underpin the inherent issues of validating your websites through automated web services/tools and how using these tools to meet certain requirements can miss the point entirely.

Current Practices

Before we begin critiquing the valiant efforts that our noble code validators undertake (they have good intentions at least), it’s important to note that with all things in life, a balance must be struck between the practical application of validation and common sense.

We live in a modern era of enlightened thought where web standards have become a white knight, always charging towards slaying code which fails to best represent our work.

But while current practices actively request and promote using these validation tools, no web-based tool is a substitute for good judgment.

The above code may not validate, but it’s acceptable to use if there’s no good alternative.

The above code may not validate, but it’s acceptable to use if there’s no good alternative.

Not Using Valid Code

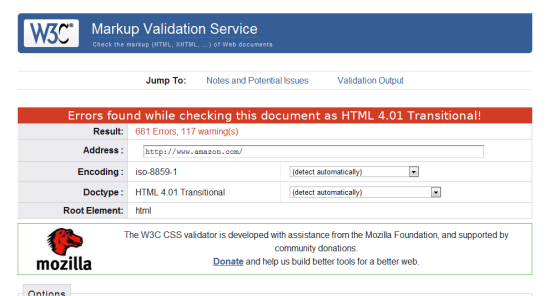

The case for under-dependence can be seen by examining the Alexa Top 100 sites and using some basic W3C validation tests.

The eye-watering number of errors these popular sites produce (which escalate into the hundreds) is rather unsettling for some.

The problems for those ignoring validation altogether has been well-documented to the detriment of end users (as has the justification for following web standards) and as ignoring validation entirely makes you as guilty as those using it as a crutch, it’s worth recommending not to forsake these tools even with their shortcomings.

Amazon.com’s front page doesn’t validate, but it doesn’t mean they don’t care.

Amazon.com’s front page doesn’t validate, but it doesn’t mean they don’t care.

Blindly Following the “Rules”

The case for overdependence is something we need to worry about too.

Those who form drug-like addictions to making everything validate or meet a certain criteria just to please an innate need for approval are on the rise.

While ensuring your code validates is generally a good thing, there are professionals who take it to such an extent that they resort to hacking their code to pieces, ignoring new and evolving standards or breaking their designs just to get the “valid” confirmation. Quite a price for a badge.

And there are even people who think validation automatically means everything’s perfect, which is worse.

There are a lot of tools out there, but you should be wary about which you rely upon.

There are a lot of tools out there, but you should be wary about which you rely upon.

Context is King

The thing about validation tools that beginners (and some seasoned professionals) often overlook is the value of context.

The most common problem that validation tools encounter can be summed up in the sense that they are only machines, not humans.

You see, while checking if the code you wrote is written correctly, on the surface, may seem like a simple task, that sites meet disabled users’ needs, or that text on the screen is translated properly — the very obvious truth (for those who understand the mechanics involved) is that the complexity of how humans adapt cannot be replicated effectively.

What does this design say to a machine? Nothing! It only sees the code and that’s it.

What does this design say to a machine? Nothing! It only sees the code and that’s it.

You Can Make Decisions That Robots Can’t

If you’ve seen the “The Terminator” movie, you probably have a mental image of a not-too-distant future where machines can think like humans and therefore make decisions based on adaptive thought processes, such as being able to intelligently and emotively know what makes sense.

But unlike that film, the levels of which such tools can understand context and meaning (beyond what’s physically there) simply doesn’t exist today—though that’s probably a good thing as we don’t want the W3C validator going on a rampaging killing spree against <blink> tag users, right?

There may be a time where machines are as smart as humans, but that’s not today.

There may be a time where machines are as smart as humans, but that’s not today.

Code Validation

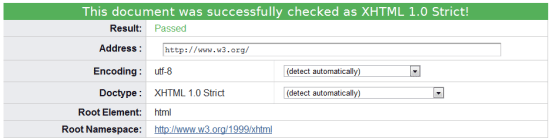

The most notable form of code validation in use today is that of the W3C HTML and CSS validators.

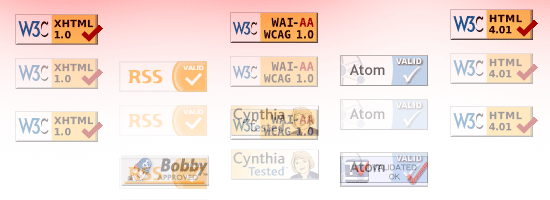

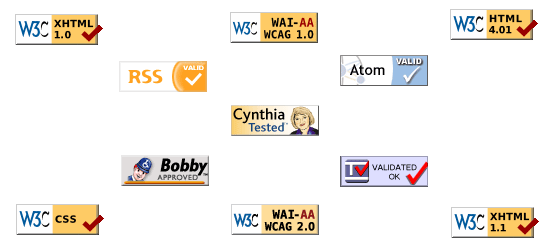

The level of obedience from some designers and developers to ensure their code validates is best reflected in the way many websites actually proclaim (through the use of badges) to the end user that their code is perfect (possibly to the point of sterility).

Proclaiming the validity of your code doesn’t mean what you’ve produced is perfect.

Proclaiming the validity of your code doesn’t mean what you’ve produced is perfect.

This reminds me of the way software developers proclaim awards from download sites as justification to use their product. As I’ve mentioned previously, however, the W3C validator (despite its association) is not perfect.

Failing Because of Future Standards

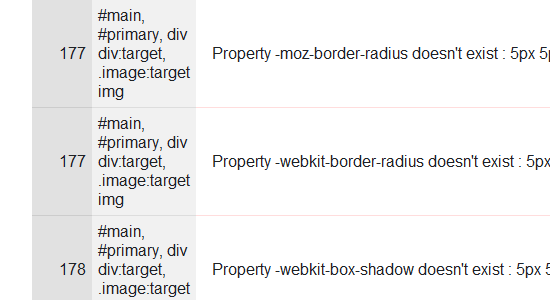

It’s an established fact that the W3C validator not only examines the structure of your site but the elements or properties themselves (though they don’t understand semantic value!).

The key issue with such due diligence from these tools is that elements which are not recognised (such as those of upcoming standards like CSS3 or equally valid proprietary extensions) are often misinterpreted by developers as “unusable” or “not approved” and therefore get rejected.

Taking Stuff Out For The Sake of a Badge

It seems rather amusing to me that people are willing to omit the value of somewhat acceptable but non-standard code — CSS3 attributes specific to particular browsers, for example — to satisfy the validators, like they’re trying not to anger the Tiki gods.

What ends up happening is the validators themselves make it seem like legitimate practices which defies convention are automatically wrong, and this results in a strange psychological condition in which people too quickly limit their own actions for the sake of a machine (or the ideology it provides).

While it makes sense not to use deprecated/future-standards code, validators simply can only test against what they know.

Nothing says: “I want approval” like these well-known badges of honour from the W3C.

Nothing says: “I want approval” like these well-known badges of honour from the W3C.

It should be made quite clear that people who proclaim HTML and CSS validation on the page are doing so to make themselves feel better. Unfortunately, none of your users (unless you cater specifically and strictly to web designers and developers) are likely to know what HTML even is, let alone understand or trust what the fancy validator badge is telling them!

Web Accessibility Validation

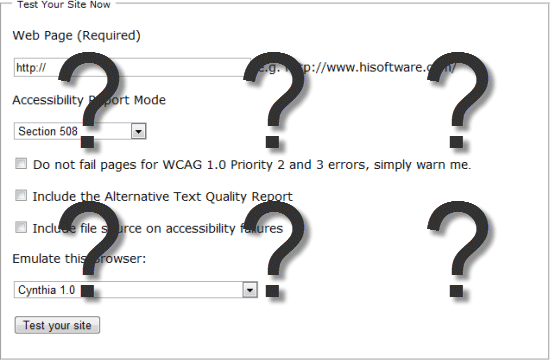

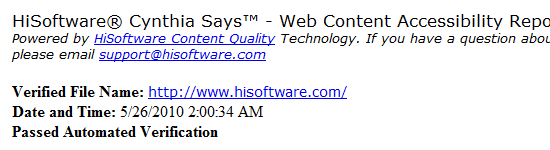

If you want a case where validators totally miss the point and where their limited testing ability is abused (to proclaim the work which is being tested against is complete), you need look no further than the accessibility validation services like Cynthia, the now debunked “Bobby” and their kin.

One key issue with validators are that they can only test against what they can see (in almost all cases this only accounts for source code).

While some of the issues in WCAG can be resolved with some helpful coding (like alt attributes on images), code doesn’t account for everything in accessibility.

Cynthia “says” your site meets WCAG guidelines, but it’s often missing several points!

Cynthia “says” your site meets WCAG guidelines, but it’s often missing several points!

The Only Way to Test for Accessibility and Usability is through People

Accessibility and usability are highly subjective issues that affect many people in many different ways, and often the way code is presented (or even the content) does not establish where key problems may lie.

Too often beginners actively use the checklist nature of these services to claim their work is accessible on the basis that a validator covered what it could (omitting the complexities which it cannot account for – such as the sensory criteria and their inhibiting factors).

This key lack of understanding and the wish for a quick fix showcases that reliance of these tools isn’t ideal.

How many validators can tell you how easy to read your content is? How many of them run a screen reader over the top of your site to denote the way a blind user may find your information?

While some factors can be mechanically replicated, the problem is the tools primarily focus on code alone and therefore miss the bigger picture (and those who rely on them also get caught up in this lack of awareness).

Without the background knowledge of how such web or software applications function, a scary number of people simply use them as an alternative to properly learning what they’re doing.

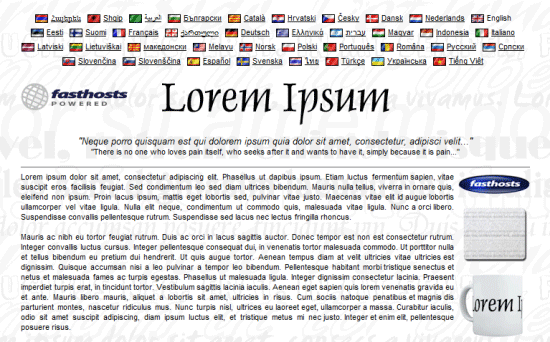

Do you speak Latin? No? This content would pass as accessible, readable and valid!

Do you speak Latin? No? This content would pass as accessible, readable and valid!

The state of accessibility tools is so bad that I advise people not to use them in favour of proper human checking.

The myth that tools can do things at an equal skill level of a human is far from the truth and while the W3C validators can be helpful, accessibility tools are too biased to be credited.

Translation Troubles

Confusion (as denoted above) in relation to such validation tools comes in many forms.

Whether it’s the mystical messages the W3C validator produces (which beginners may not understand), the lack of fair warning that these tools should be used “as part of a balanced diet”, or that these tools are often much more limited in what they can offer than you would be led to believe.

One of the more comical examples of automated tools going crazy can be seen through translation tools such as those provided by Babel fish or Google, which again proves that nothing is better than humans.

Google Translate is popular amongst websites for giving “rough” language translations.

Google Translate is popular amongst websites for giving “rough” language translations.

One of the key elements of human languages is that words can have more than one meaning (and deciding which instance is in use can be tricky for machines – a case of context).

In accessibility, the issues of vision can be anything from total loss of eyesight right down to a case of color blindness. Because of this, a language translator will simply go for a literal meaning of the word rather than the context in which it’s used which can reduce your content into a scrambled illegible mess which doesn’t help your visitors (especially if they have learning difficulties).

While of course translation tools aren’t code validators, they do in fact perform a similar service. By taking a known list of criteria (whether code, words or something else), they attempt to check that something accurately portrays what it’s intended to.

If, however, you use something it doesn’t expect (like a new word in translation tools or a new property in the W3C validator), it will report it as a failing on your behalf.

Such reliance on validation tools for “perfect” results is therefore unjustified and can limit yourself to the detriment of your audience.

A Translation Exercise to Test the Idea

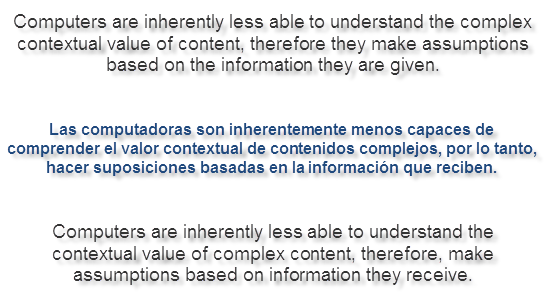

If you take a block of content from a website, paste it into Google Translate, translate it to another language, and then translate it back into English, you’ll see for yourself how badly these validators of content conversion are at the job. It can give you hours (if you’re really that much of a geek) of comedy in a few sessions!

See how the same sentence has been wrongly translated? It’s not uncommon!

See how the same sentence has been wrongly translated? It’s not uncommon!

The Silver Bullet

Knowing that validation tools are far from perfect is an important lesson to learn. Many people assume that such tools are an all-knowing oracle that accounts for everything your users or browsers may suffer.

While it’s wrong to say that these tools aren’t useful, it’s important to understand that the validation tools should not be used as a guarantee of accuracy, conformance or accessibility (in your visitor’s best interests).

A valid site should never be achieved if it sacrifices the progression of web standards, unjustly acts as a badge of honour or attempts to justify the end of the build process.

Knowing how and when to use code and the difference between right and wrong is a tough process we all undergo during our education.

The truth about validators is that sometimes being invalid is the right thing to do, and there are many occasions where a “valid” website is nowhere near as valid as you might like to think it is in terms of code semantics, accessibility or the user experience.

I hope that all of this will serve as a wakeup call to the generation of coders who either ignore or abuse validation services.

These tools are not a silver bullet or a substitute for being human!

Related Content

- Five Technologies That Will Keep Shaping the Web in 2010

- Best Practices for Hints and Validation in Web Forms

- What is The Future of Web Development?

-

President of WebFX. Bill has over 25 years of experience in the Internet marketing industry specializing in SEO, UX, information architecture, marketing automation and more. William’s background in scientific computing and education from Shippensburg and MIT provided the foundation for MarketingCloudFX and other key research and development projects at WebFX.

President of WebFX. Bill has over 25 years of experience in the Internet marketing industry specializing in SEO, UX, information architecture, marketing automation and more. William’s background in scientific computing and education from Shippensburg and MIT provided the foundation for MarketingCloudFX and other key research and development projects at WebFX. -

WebFX is a full-service marketing agency with 1,100+ client reviews and a 4.9-star rating on Clutch! Find out how our expert team and revenue-accelerating tech can drive results for you! Learn more

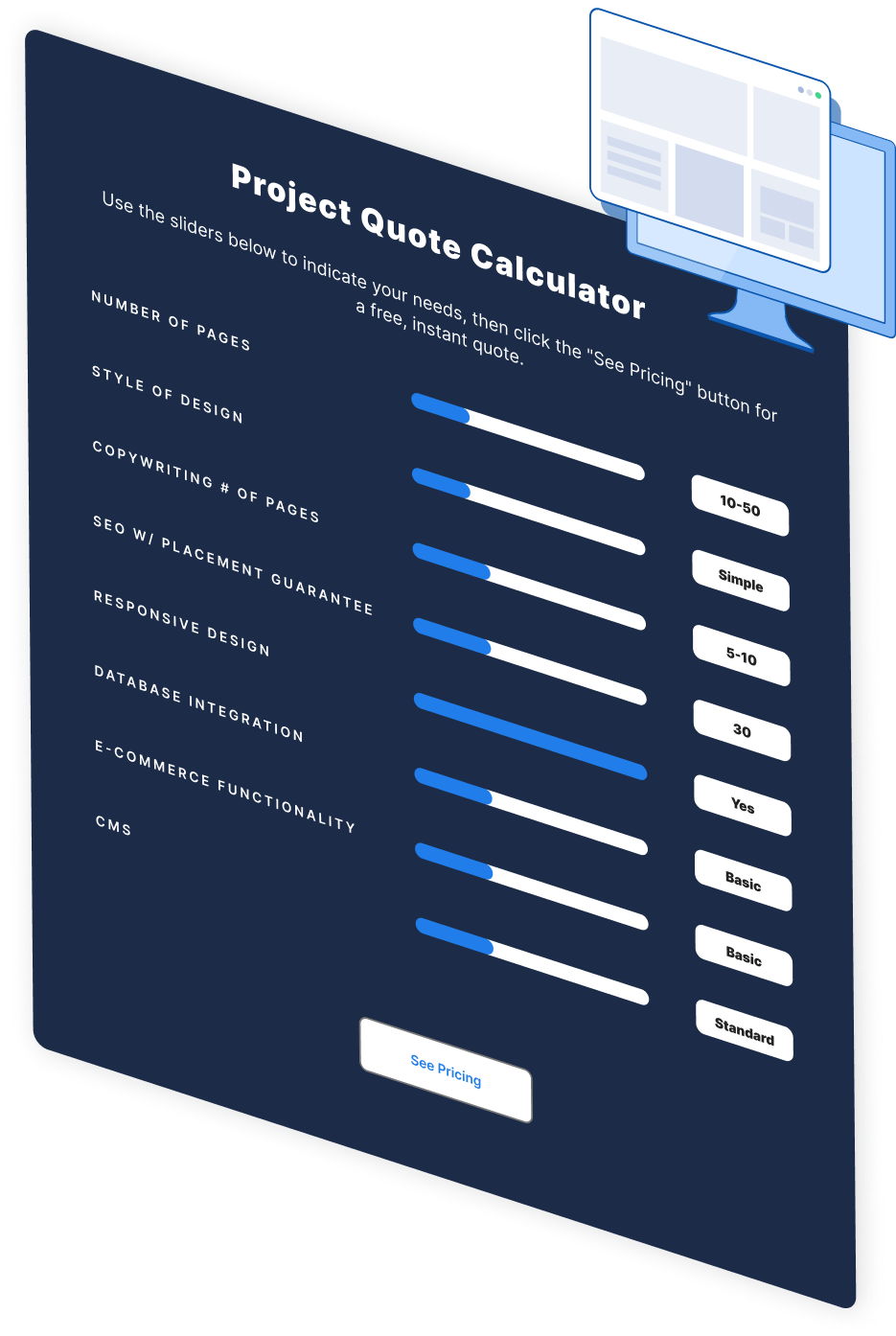

Make estimating web design costs easy

Website design costs can be tricky to nail down. Get an instant estimate for a custom web design with our free website design cost calculator!

Try Our Free Web Design Cost Calculator

Web Design Calculator

Use our free tool to get a free, instant quote in under 60 seconds.

View Web Design CalculatorMake estimating web design costs easy

Website design costs can be tricky to nail down. Get an instant estimate for a custom web design with our free website design cost calculator!

Try Our Free Web Design Cost Calculator